RECOLLECTIONS OF 24 YEARS OF TEACHING AT ST AUGUSTINE’S, 1971-1995

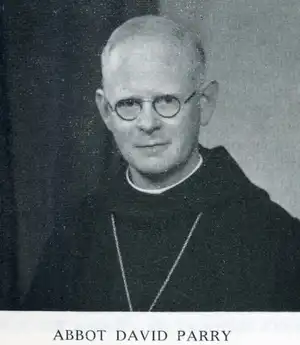

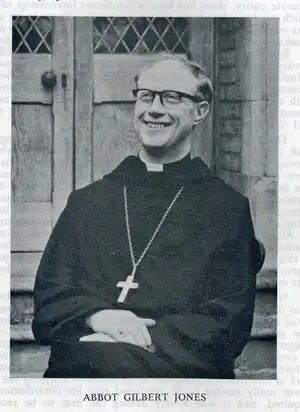

I have chosen the title, As I Remember It, deliberately since details fade or become distorted as the years go by and so the memory can deceive one. The big question, therefore, is: How reliable is my memory? I have based the recollections which follow not only on what I think I remember but also on such personal (not school) documentation that I have held on to since retiring as well as on what is recorded in The St Augustine’s Magazine as I have kept all the copies I received during my teaching years. The photographs of the monks have been scanned from the magazines.

About fifteen years ago I used these various sources to write for my family an account of my time at St Augustine’s and that has been the basis of what follows – as I remember it.

This is not to be regarded as a history of the school over those years but rather as part of my personal history even though the two overlap.

INTERVIEW AND APPOINTMENT

I still remember the first time that I met Father Bernard, even though it was 44 years ago. To be exact, my first encounter with him took place on 31st May 1971, Whit Monday that year, when he had invited me to Ramsgate for an interview to fill a vacancy for an English teacher.

It was a meeting that nearly didn’t happen, in which case my future and that of my family would have been very different. Father Bernard, as he then was, had advertised in The Times Educational Supplement dated 9th April for a master to teach English and I wrote applying for the post on 12th April. It was 5 weeks before I received a reply – Father Bernard’s letter was dated 18th May. By then I must have given up hope. In that letter he apologised for the delay but after he had placed the advertisement, he said, he began to think that he might be able to cover his needs by reorganising his existing staffing and so might not need another teacher. Fortunately for me he liked the fact that I had graduated in Economics as he thought that that might be useful at St Augustine’s, so he did invite me to Ramsgate for an interview after all.

As I had to travel from Cardiff, it was necessary for me to stay overnight, or perhaps it was even two nights. It being the Whitsun weekend, the school had a short half-term break until the Wednesday and there were few people around so it had been arranged that I would stay in the staff accommodation at 3 Grange Road.

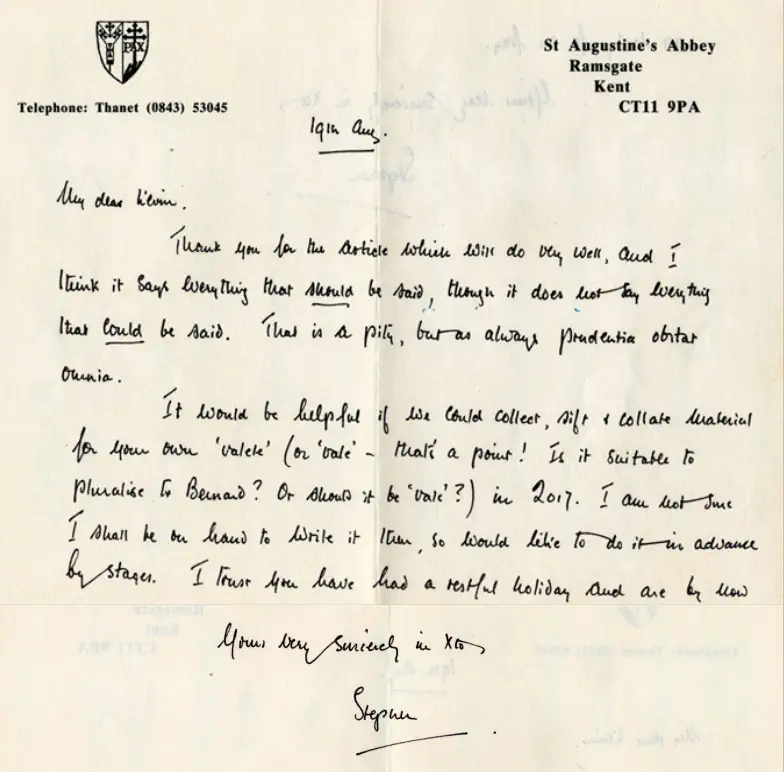

Father Bernard interviewed me next morning. I remember it well. His study was dark and gloomy and smelt of tobacco smoke – pipe tobacco. Father Gilbert Jones, later Abbot Gilbert, looked in by arrangement, very informally, to cast an eye over me but Father Stephen Holford couldn’t as he was in bed unwell. (They both taught English, which was why Father Bernard wanted them to form an opinion.)

Father Bernard took me on a tour of the school, though I remember few details apart from the fact that a couple of boys were playing badminton in the hall – most were away for the Whitsun break. Then he drove me over to Westgate for a tour of the buildings to which the college would be relocating for the new academic year in September. This was the Les Oiseaux Convent School run by the Canonesses of St Augustine who were closing the school. I was very impressed.

During my overnight stay at Ramsgate I had my meals with such of the staff as were there. One of these was Mr Blaney, who, I was told, had been teaching at the school for 18 years, which seemed like an eternity to me. He actually stayed with the school/junior school until he retired at the end of the summer term in 1985, having served the school for 32 years. I was also told that Miss Leahy had been there even longer as she started at the school in 1951 and she continued until 1994, almost until the closure of the two schools in 1995, though her later years were only part-time. That made 43 years of service.

Then it was time for me to go back to the station for the return journey to Cardiff to await the outcome of the interview. On 15th June Father Bernard wrote to offer me a post and on 20th I replied without delay to accept it. In the letter of appointment I had also been asked to run the school library and produce the school magazine and I agreed to take on both but my response to the latter was clearly not enthusiastic – “I will willingly take charge of the library and do what I can for the School Magazine.” Little did I think at the time that I would be at St Augustine’s for 24 years – or that I would spend the last eight of them as headmaster.

I took up residence at St Augustine’s in Westgate a few days before the start of the Michaelmas Term and items were still being put into place in readiness for the boys’ return and I, along with others, lent a hand. A few boys also were there and as we moved lockers around, someone asked where Michael Heinemanns had gone. Miss Bevan, the matron, said that she thought he had gone to Dreamland. Knowing nothing about Margate and its visitor attractions, I assumed that she was saying that he had gone to his room to lie down and have a sleep whereas in reality he had gone to the amusement park of that unlikely name. Fortunately I didn’t have to make a comment that would have shown up my ignorance.

I wasn’t the only staff newcomer that term. Confusingly there was another Doherty, Jack Doherty, who was the Biology master. Even more confusingly he pronounced his surname in the Irish manner (and with an Irish accent) whereas I pronounced it in the English manner (and with an English accent). Everybody soon got used to it, though. Jack stayed just a year, one reason being that he had soon got to know one of the Les Oiseaux teachers, Prunella Eaton, well enough for them to become engaged. That was quick going.

Another newcomer was Mr Duxbury, a young graduate who taught Physics. Like me, he played table tennis and we enjoyed many a game in the basement TGC – the Table Games Club, a name brought over from Ramsgate which eventually faded from use because traditions don’t always take root in a new environment.

Also there was Miss Sheila O’Halloran, who was the new secretary to the headmaster. In my search for somewhere for my family and me to live, I had called at various local estate agents, including Cole & Hardie in Garlinge where she was working prior to taking up the post at St Augustine’s, so we actually met beforehand without realising that we were shortly to be colleagues. Many Old Boys will know her as Mrs Mulvihill, of course, as she married later in the 1970s.

Since I have indicated that I was house-hunting, I should state that on receiving my acceptance of the post offered, Father Bernard mentioned the possibility of a house being available. This was the large property in Osborne Road, Westgate, often known as the Red House but which officially was called Allandale. The back of it looked on to the school building, separated from it only by a football pitch. The Canonesses of St Augustine had used the house as additional boarding accommodation for sixth-formers, I think, and so the larger rooms had been divided with plasterboard partitions. My wife and I had a look at it on our visit to Westgate to get to know the school and the area during the summer holidays but we decided against making it our home. It was not suitable for us as it was – even the sitting room was divided, and the kitchen would have needed a lot doing to it. Besides, we felt that it was too big and probably draughty so instead through Messrs Cole & Hardie we decided on a newly-started house in Brunswick Road, Birchington, less than two miles from the school. Only the foundations were down and it would not completed until some weeks into the new year so for the Michaelmas and Lent terms I had to leave the family in Cardiff and be a resident master in the college, going home occasionally at weekends.

Allandale was owned by Mr Ivor Reed, who was said to own half of Westgate, and the Canonesses rented or leased the Red House/Allandale on favourable terms from him for their school use. The arrangement continued with the Benedictines when they took over, and carried on right until the school closed in 1995. As my wife and I didn’t want it, the house was used by the school in that first year to accommodate bachelor lay staff. I think it was then used for senior boarders but eventually, after modifications had been made, it became a staff house for Mr John Bond, a Maths teacher. He came from Malta and before he joined the staff he had had a boy in the school. Later, his younger twin boys, Trevor and Ian, also attended St Augustine’s. Mr Bond had heart trouble and retired early in 1991 but died in October 1995.

Though St Augustine’s College was organised on house lines, there was no actual residential significance – the boys did not live in separate houses as in many boarding schools. When I started in 1971, two of the houses (Alcock and Bergh) were for boarders and the third, Egan, was for day-boys. Years later they were rearranged so that all three had both boarders and day pupils. On taking up my appointment, in addition to editing the school magazine and running the library, as I was a resident master I was made deputy housemaster of Alcock under Father Gilbert Jones. What later became the Upper Sixth corridor was staff accommodation, which became my second home for the next two terms. Each of us had a bedroom on one side of the corridor and a separate study directly opposite. It suddenly dawned on Father Stephen that my room, and therefore I, “didn’t have an opposite”, as he put it. Instead he gave me the use of a room that he himself had originally been going to use which was in the corner between a small kitchen and the boys’ senior common room. It was a pleasant room which I continued to have the use of for many years even after I became non-resident.

THE FIRST YEAR

That first year was a curious one. Thinking back, I have to say that administrative control at St Augustine’s was too relaxed in various ways and many of the teachers seemed to have relatively light timetables – including me. Collectively we were slack about lessons, turned up late, and in the summer might take a class outside when the weather was good, which meant in practice that little work was done in that lesson. Sometimes teachers cancelled a class, perhaps to let the boys watch a house match on the playing field we used next to King Ethelbert School along the Canterbury Road. On Wednesdays the Upper Fifth had a double lesson for O Level Economic and Public Affairs. A colleague took the first of the two lessons for the Public Affairs (British Government) part and I had the next one for the Economics section of the syllabus. More than once I was annoyed because the class wasn’t there – they had been taken to watch a house match, and they weren’t going to come back for me.

Yet another example of the problem was staff room cricket, which was played with a tennis ball. A leg of a chair or table might represent the wicket and runs were scored according to where the ball was hit. It was fun but unprofessional. Mea culpa, mea maxima culpa.

Some teachers were used wastefully in another way – teaching the juniors at Assumption House in that first year at Westgate was part of their programme and travelling to Ramsgate and back took up a disproportionate amount of time. The travelling ended the next year when the junior school moved into the buildings at Westgate. That some of the teachers taught in both the junior and senior schools was one aspect of staffing policy. By and large the two schools had their own teachers who taught exclusively in one or the other, but there was an overlap in some cases, particularly in the science subjects. There was also some scope for interchange, some teachers moving from the college to the junior school and some the other way around. In all my 24 years I taught only in the senior school.

When St Augustine’s moved to the Les Oiseaux site, work had to be done to adapt it to our needs. The grounds, for instance, required much work as the Les Oiseaux girls used less playing-field space than the boys and what was available was much less than we needed. The area that had been the girls’ sports field became our main rugby pitch and their four tennis courts (asphalt) adjacent to Allandale were retained and used by the boys throughout all the ensuing years. The field between the science laboratories and Allandale had been a cabbage field, I think, and that was seeded with grass to provide us with another football or rugby pitch. At the back of the school, a dividing wall was taken away and trees and shrubs were removed to give enough space for a further football or rugby pitch, and the cricket square was strategically placed so that it didn’t suffer too much wear and tear from the winter games. In summer, the line where the wall had been could be clearly seen as the grass soon became brown in dry weather on account of the shallow depth of soil over the remaining foundations.

Inside the building, rooms often changed their use over the years. The library, for instance, was housed in four different places at different times. Improvements were made to suit our needs, but the main one in those early years was the construction on one level of a much-needed block of four classrooms, with cloakroom space and toilets. This block linked with the main building but was of lightweight and ‘temporary’ construction with a pitched felt roof. It was not very robust, and with boys pushing and shoving each other as they often do, a shoulder hitting the plasterboard walls with some force could easily create a crack, dent or hole – and often did. Over the years much money had to be put into repairing damage and strengthening the structure.

That first year of the college at Westgate was a more difficult year than I realised at the time. To get a full picture, it is necessary to read the article entitled Chronicle in the St Augustine’s Magazine dated 1971-1972. As the editor of the magazine, I thought the article (by Father Stephen Holford) was undiplomatic and bad public relations, so I prefaced it with a note trying to moderate any adverse effect it might cause. That upset Father Stephen and more will be said about that later. As a newcomer I should have been more considerate.

The problems he referred to occurred mainly because the senior boys did not have the emotional maturity to adjust to the presence of girls in their midst. Fifty or more Les Oiseaux pupils who were due to take their O or A Levels in 1972 stayed on with some of their teachers, including some nuns. This was to minimise the disruption to their studies as it would have been very hard on them if they had had to find new schools for the second year of their two-year courses. They were accommodated in Tower House, which was, of course, off-limits to the boys. Their lessons were separate too, except for Religious Studies. These classes were given by Father Theodore Richardson, a monk who was a Doctor of Canon Law of Louvain University in Belgium. Other members of staff were encouraged to attend these sixth form lessons if they were otherwise free, and in the early days I went along. The lessons took place in the room near the chapel which started off as the library as it was lined on three sides with glass-fronted bookcases. It eventually became the staff room. On one occasion one of the girls, Kate Bishop, spoke up and told Father Theodore that he was talking above their heads, but it had no effect as he dismissed the criticism on the grounds that he had to challenge them to think on a higher level. The real problem, however, was that Father Theodore’s talents were wasted in the school; he was more suited to lecturing in a university, theological college or seminary.

I didn’t fully realise the nature of the difficulties of the year as the situation was totally new to me and therefore I regarded it as normal in that type of school. It was also a time when the boys tended to be on the ‘bolshie’ side. The student unrest of 1968 on the continent had occurred not long before and that sort of attitude lingered. Also, I think there was resentment about the somewhat Spartan regime and conditions in the school.

Nevertheless, I felt at ease. There were, however, individual occasions when things went wrong for me, and one I remember clearly. I was taking an English lesson with one of the O Level classes and there was a bit of chat back and forth between the boys. I was walking down one of the aisles between the desks and gave Michael Russell a light flick across the top of his head because of his persistent talking. His face reddened, his eyes began to glisten, and I realised that he was very angry at my action.

“You’d like to hit me, Russell, wouldn’t you?” I said.

“Yes, sir,” was his reply.

“Keep your self-control. Good man,” I said. Or words to that effect.

And I faced him out and saw the tension draining away from him. The situation had been defused and we carried on as normal. But the incident had taught me a lesson that I didn’t forget; I would never get myself into that sort of situation again.

Talking to the boys outside of class could also be amusing sometimes. I was in conversation with John Bunn of the Fifth Form when the subject of marking prep and classwork came up. I made the observation that no teacher enjoyed marking but indeed found it tedious, at which he expressed surprise.

“I would have thought that it was the best part of being a teacher,” he said, “ – exercising power and all that.”

Perhaps some teachers do enjoy wielding power, but not that way.

On another occasion, during the leisure period between the end of afternoon school (4.30 p.m.) and the evening meal (5.45), I came out of my study on the top floor of the main building, which, as I mentioned, was next to the upper school common room. This had two table-tennis tables and a quite good full-size billiard and snooker table, and as I passed the door I saw David Cook, another fifth-former, sitting on the billiard table just idly swinging his legs. He was alone in the room and looking rather morose so I went in and asked him what the trouble was.

“It’s boring, i’n’t it?” he said. “There’s nothing to do.”

“Oh,” I saidbrightly, “in that case we had better see if we can organise something for you all.”

“What!” he said. “Not likely! This is our free time!”

In staff meetings I had a lot to say about what I felt we could be doing. One of the things which was introduced in consequence was an inter-house competition covering various subjects – English, Art, Music, ….. It went down well and Father Stephen was very complimentary about it in the Chronicle article already referred to. His one criticism was that the event had been too long, and he was quite right, so in future years it became purely an English competition with written and spoken events. It continued annually, virtually until the closure of the school, in an unchanged format once it had been polished to what seemed an ideal structure, and I ran it until I became headmaster in 1987.

In 1972, Abbot Parry resigned as Abbot of Ramsgate with effect from Easter and Father Gilbert was elected his successor. He therefore had to give up his teaching commitments. Although I was by then a non-resident master (in March 1972 my family and I had moved into the house we had bought in Birchington) I was nevertheless made full housemaster of Alcock (a house of boarders) in succession to Father Gilbert, now Abbot Gilbert.

THE FLOOD

It was Friday 21st September 1973 and I walked to school as usual because the heavy overnight rain had now stopped. However, when I reached the school I could see that something drastic had happened. As I turned in through the gate I saw a fire-engine with its hoses pumping out water, and there was much activity. A look inside the building and a walk along the cloisters confirmed it – all was chaos. Wet and mud and debris were everywhere. The building had been flooded.

Prior to the downpour we had had a long period of dry weather and the ground was very hard, so hard that it could not absorb the heavy overnight rain. In consequence the water ran off the farmland and built up in the dip against the wall at the back of the college in Lymington Road until it suddenly broke under the pressure. The water must have flowed like a tidal wave across the open playing-field and smashed down into the basement through the windows. From there it had gushed up into the ground floor of the building to a depth of over two feet, perhaps even three. (The ‘high tide’ mark was still visible in places even when the school closed in 1995, particularly on the oak doors of the staff dining-room.) The railings which edged the drop to the basement windows were torn out of their foundations and were a mangled wreckage at the bottom of the bank by the windows. One would not have thought it possible that so much water could have built up that it still had that power after racing at least 100 yards across the playing field. In fact, if I had not seen it I would not have believed it, but there was the evidence in front of me.

The part of the basement where the water poured in we called the crypt though it bore no resemblance to one except for being below the main building. It was used mainly by the junior school as a recreation area and for study. Another, and separate, part was used as a store, and boilers for heating were in other sections. Altogether it was quite an extensive area and that and the ground floor from Mr and Mrs Edwards’s adjoining house at the western end of the front cloister to the end of the rear cloister, including the birds cloister, were the areas affected. They included the headmaster’s study, the reception room, the kitchen and the dining-rooms, but the chapel largely escaped – the water came within an inch of the top step inside the chapel doors. If it had gone any further it would then have poured down through the grating in the floor into the boiler room below and the damage would have been significantly greater.

A salvage operation was going on when I arrived but it was clear that it was impossible for the school to function in any way approaching normal and arrangements were made to send most of the boys home. After their departure the clearing-up operation continued with the help of the sixth-formers, “ … who set to work with a will and literally dug the College out of the mud,” as Father Bernard stated in his Headmaster’s Report read at Prize Day in December 1973 and printed in the April 1974 issue of the school magazine.

Besides the clearing up, another problem that had to be dealt with was drying out the structure of the building, and the R.A.F. at Manston came to our aid with large paraffin heaters that looked like small jet engines (and sounded like them). There were two of these in the front cloister, for example, blasting out hot air. The wonder is that it was only ten days before the boys were able to return and school life continued.

That overnight rain should have such a devastating effect is astonishing but I believe that the amount of rainfall was itself astonishing. Memory tells me that it was as much as EIGHT inches. If that amount stretches belief, Father Bernard’s Headmaster’s Report mentioned that we had had “… one whole year’s rainfall in twenty-four hours.”

DEBATING

An important aspect of the broader curriculum was debating. This was for the whole school and it took place approximately every three weeks on Friday afternoons during what would otherwise have been the last two lessons of the day (from 3.15 to 4.30). There were two separate sections, one for the Upper 4th and Lower 5th and another for the Upper 5th, Lower Sixth and Upper Sixth. According to the school magazine, Mr Duffy restarted debating (it had taken place in Ramsgate days) in September 1972 when he joined the staff to teach O Level English and A Level British Constitution as well as to become the boarding master having a flat accessed between the classrooms that came to be designated Tower House Front and Tower House Back. It also shows that Father Benedict was responsible for the lower school debates but eventually I took them over from him.

In a way, running the debates for the lower school was the more difficult task as the boys were less mature, were less experienced, had less confidence, and had a wider range of intellectual ability and fewer ideas than those in the upper school. Overall the system worked reasonably well – except for one thing. Mr Duffy sometimes forgot and had to be reminded when a debate was due with the consequence that nothing had been organised. I think it was in December 1977 that eventually there was something of a coup d’état as even the boys were fed up with it. One of the prefects, a namesake of mine but no relation, Chris Doherty, approached me on behalf of the seniors with the request that I take over their debates. That put me in an awkward situation but I raised the matter higher up. The outcome was that I did take over from Mr Duffy and in due course reorganised the debates on a whole-school basis, taking in both the upper and lower school. Building it around an inter-house competition to spark interest and stimulate participation worked and I felt that the debates were looked forward to, were enjoyed, and had a positive educational effect.

Another innovation was that I designated the head boy as Chairman of Debates, the first being Louis Kopieczek, The head boy did not belong to any house and so was theoretically neutral, which the chairman needed to be. There were one or two occasions when we even had a staff debate. In one of them, I think it was the one in 1982 on the motion That Left is Right, Robin Edwards spoke first proposing the motion and I spoke next for the opposition. Mr Edwards had spoken for a long time – too long, I considered – and in my speech I took him to task for it. I described him as having spoken “at near-Theodorean length,” a comment which brought forth a roar of approval. Everybody knew that I was referring to Father Theodore. When it was his turn to say the weekly school Mass, Father Theodore’s sermons went on interminably, or so it seemed. What added to the delight of the boys was that Father Theodore was attending the debate. He took it in good part, of course.

The debates scene expanded in 1981 with the start of the Thanet Schools Sixth Form Debates. When we attended our first one in the Castle Trust centre at Ramsgate harbour, our sixth-formers came away full of confidence. “We’ve got the know-how!” exclaimed Timothy Pitt-Payne, who went on to become a barrister. He was quite right; our internal debates had given it to them. Then a competitive event between the Thanet schools in the Council Chamber in Margate was introduced in 1982. It was known as the Aitken Cup because Jonathan Aitken, then the M.P. for Thanet South, presented a small trophy and adjudicated the event. Usually between six and eight schools participated, the first such event being won by the Ursuline Covent School. St Augustine’s, however, went on to be the first to win the Aitken Cup three times – in 1983, 1984 and 1992.

When we returned from these Sixth Form debates in winter, the school was dark with not a sound to be heard. I let the boys in by the side door near the school office and shepherded them in so as not to disturb the peace and quiet. The silence could almost be felt if not heard. Were there really 200 normally noisy boys somewhere in the building? It wasn’t just the silence but also, again, the impact of night. It was past bedtime so all the lights were out and (except when the moon was shining) the chapel cloister was deeply dark. The birds cloister was a little less so, while the front cloister was palely lit by the distant Canterbury Road street lights penetrating the lancet windows and casting gentle shadows on the large polished floor tiles. To be apparently alone there at night wasn’t at all disconcerting for one seemed enfolded in something of the spiritual serenity of eternity. Perhaps the atmosphere worked on the over-vivid imaginations of some of the boys, giving rise to the story that the ghost of a nun walked the cloisters. All that I sensed was a deep peace.

DRAMA

While the school had been at Ramsgate, Father Martin Symons had taken a keen interest in producing school plays but he was not on the staff at Westgate. Father Gilbert, however, had a background in the theatre and television before becoming a monk and despite having been elected abbot at Easter he, with the help of Miss Monica Cowell of the Les Oiseaux staff, staged a performance of The Hollow Crown, described on the title page as “an entertainment”.

Productions were fitful after that, the next being entertaining if not entertainments in the same sense as The Hollow Crown – operettas by Gilbert & Sullivan. In December 1975 there was Trial by Jury produced by Vincent Hamilton, the 6th Form Mathematics master, and then in 1978 Pirates of Penzance directed by games master Mr Logan and Biology master Mr Chilton. A year later, February 1979, Father Peter Wilkie, who was a secular priest, not a monk, directed the musical Oliver! for the junior school and then it was back to Gilbert & Sullivan with Mr Duxbury’s production of H.M.S. Pinafore. Then we had the changing of the guard with Father Laurence, later Abbot Laurence, producing the rather deeper G & S, The Yeomen of the Guard, in May 1982. Next, in March 1983 Father Laurence took it to a higher level by going to Shakespeare for Richard III followed by The Merchant of Venice in March 1984. Abbot Laurence was always a Shakespeare enthusiast and to this day will quote impressively from the plays if you give him half a chance. What surprised us in those productions was how boys who might be struggling a bit in class handled Shakespearean drama with skill and confidence.

There were other productions in other years, including more Shakespeare from Father Laurence (Macbeth, Henry IV-Part 1, A Midsummer Night’s Dream and The Tempest) and lighter entertainment from our bursar Mr Gransbury who produced a version of music hall entitled The Good Old Days in March 1990 and in February 1993 a double production with shortened versions of H.M.S. Pinafore and The Mikado. In 1994 and 1995, drama, or at least stage drama, faded from the scene at St Augustine’s, or, if it didn’t, my memory of it has. Truth to tell, my memory had faded already as I had to extract from the magazines much of the detail in this paragraph but it needed to be done to acknowledge the sterling efforts of those involved.

It was all the more commendable as it was done without a stage, a temporary one being assembled from do-it-yourself staging, which was also used for the Prize Day platform. Basic, but it served the purpose.

MAGAZINE EDITOR

You may remember that I stated that when I was appointed to the staff Father Bernard had asked me to take on responsibility for the library and the school magazine.

For much of its existence the school magazine had been published each term but the move to Westgate in September 1971 disrupted preparation of the issue for the Summer Term of 1971 and a slim edition appeared dated Autumn 1971. Nominally I was the editor but most of the work was done by Father Stephen Holford. After all, I had not been at the school for the term in question so it was a virtually impossible task for me. The next issue, which covered the whole of the academic year 1971-1972 and was so labelled, was my work but it too was slim and not very distinguished. Worse, I managed to offend Father Stephen, the hurt staying with him for many years as I shall explain later.

I didn’t feel comfortable with producing the magazine and I certainly didn’t enjoy it, so when Mr Chesworth, who joined the staff a year after I did, volunteered to take it over, I readily agreed and Father Bernard approved the change. Mr Chesworth edited the next five issues, which now appeared twice a year instead of every term, but in his last issue (Sept. 1975) the editorial mentioned that a policy decision had been taken to publish the magazine annually thenceforth. By that time Mr Chesworth felt that his work as housemaster of Egan House gave him quite enough to do, so he handed over the editorship to Mr Peter McEnerny, who taught French and some Spanish. After producing two issues, Mr McEnerny left at the end of the Michaelmas Term, 1977, to take up an appointment elsewhere, so once again the editor’s chair was vacant. I can still picture what happened. I was in the staff room, standing facing the front of the large bookcase with wood-framed glass doors where my books and papers were stored and I was leafing through something or other when Father Bernard came up behind me and somewhat hesitantly asked me if I would take on the role of editor again. Given my first attempt at being the editor and my own feelings for the post, I am surprised both that I was asked and that I fairly readily agreed. I said that I would do my best. Thus began my second ‘ministry’.

Certain things followed. I was given to understand that the school prefects kept notes with a view to the compilation of the Diary, but, with a term already gone, I found that there was in fact nothing, so the only solution was for me to become the diarist. It was probably a bad policy but I found generally that if I wanted something done it was best to do it myself – even teachers can be reluctant to put pen to paper. So it was that Scribbler was born. I never admitted to the boys that I was Scribbler, nor really to the staff, though the fact was known. One teacher, Denis Berry, described it as the worst kept secret in the school. It was my policy to mention by name in the diary as many boys as I could – it was one thing that would get them to read it. “Am I in the Diary this year, sir?” asked Stefan Hoare. The boys certainly knew that I was the editor so I could give some sort of an answer without admitting that I was Scribbler, but I am sure that they had their suspicions. It was all part of a game.

What had started out as a necessity (keeping the Diary) became a task that I actually enjoyed, but by then I was also fairly well established as Silly Mid-on, the writer of the account of the annual cricket match between the school and the staff. My first attempt at this sort of thing was covering the staff football match in 1972, but that article was just a one-off, and the next year (1973) I wrote my first report on the staff cricket match. I did it again in 1974 and 1975, but during the academic year 1975-1976 I had leave of absence to go on an education course. I retained my interest in the activities of St. Augustine’s, however, and went along to the staff cricket match to watch, not to play. I had naively thought that nothing would be required of me and I wrote no account of it. Then early in the summer holidays, Peter McEnerny cycled to my home in Birchington to ask me if I would do so. I obliged. Thereafter writing these accounts was a self-imposed task which gave me a lot of pleasure. I knew what my aim in writing them was and I had established my style.

Apart from 1976, my year out, I always played in the staff cricket match though I was no cricketer. Indeed, not many on the staff were. Rather boldly I had volunteered to be the opening batsman in my first match in 1972, largely, I think, because it guaranteed me an innings. That first match was an odd one. The school team was all out for 45, a ridiculously low total, and I can only think that the reason was much cynicism and little seriousness on the part of the boys. When the staff batted, I managed to stay in and we reached the 46 required to win for the loss of only five wickets. I scored 19, hit the winning run, and was not out at the end. That was almost the best I ever did. Some years later (1977), Robin Edwards and I opened the innings, as we always had since that first one, and we scored 62 runs for the first wicket, at which point I was out for 20; that was my highest total. In due course I gave up my role as opener and batted lower down, and by the time the school closed I had in effect ‘retired’ from playing though I still wrote an account of the match except for the very last one in 1995. My own favourite at the moment (it could change) is Apologies to Chaucer written in 1993, the only one in verse form.

As for producing the magazine, the practice was that the editor gathered and organised the articles and information from the various sources and put them all into a shape from which the printers could turn out the finished magazine. Having done that, the editor passed the file on to Father Bernard for him to go through and take to the printers. A proof would then come back, corrections would be made and the amended proof would be returned for a second and final one to be printed and submitted to the editor to be checked. In theory all errors should have been eliminated but in practice they weren’t. Every issue is a record of human fallibility in that respect.

If I was the editor, I suppose that Father Bernard was the editor-in-chief, a function which he never actually exercised. Not once did he tell me that he thought that this article was not good enough to appear, that that one would benefit from re-writing, or that perhaps I should arrange the magazine differently and put in more (or fewer) photographs. I think that his attitude was that the editor was in charge and therefore carried the responsibility – he took the credit and he took the blame. Father Bernard expected his staff to carry out the duties assigned to them and accepted by them, or, as Robin Edwards wrote online following the news of Abbot Bernard’s death, “… as headmaster, he possessed that all too rare virtue of trusting the professionalism of his teachers and of not feeling the need to give constant direction.” However, an editor is not entirely detached as his contributors are his colleagues – I can think of one or two articles which I should have deemed not good enough and one or two articles in earlier magazines which previous editors should have judged likewise. Also, a gentle word of advice might have prevented me from offending Father Stephen in 1972. But then, to what extent did I act as editor-in-chief when I was headmaster? I cannot remember.

One thing I learned as editor was that one should not expect much in the way of feedback. Seldom did anyone tell me how much they had enjoyed (or disliked) the magazine, nor were there words of appreciation (or criticism) about the Diary or Silly-Mid-on’s efforts. I happen to think that they did like them, but to a large extent I felt that I had to get my satisfaction from the actual writing and even assume that nobody read the articles. I do, however, recall one adverse reaction, which surprised me because I had assumed that everybody understood the tone and ironic humour of the cricket articles and that they would therefore never take anything amiss. Ever afterwards I took even more care in my comments about staff and satirised myself from time to time so that no one could take offence if I made a little gentle fun at their expense. No one ever did again; that was the one and only occasion.

I remained as editor for ten years, and I derived much satisfaction from the work. Over the years, I made what I thought were various improvements in the arrangement of the magazine and introduced three new features. One was Portrait Gallery, which first appeared in October 1983 and featured four members of staff. I encouraged them to provide a photograph taken in their younger days to add interest – and perhaps appeal to their vanity as well since we all feel that we were better looking when we were younger – together with a synopsis of their careers and backgrounds. I never appeared in Portrait Gallery as a matter of policy.

October 1983 also saw the introduction of Reflections, which I did not consider a success. The idea was to invite a different member of staff each year to write an article on something of interest to him (or her) and on which he (or she) had particular thoughts. I think the first one was written by Mr Chesworth, under the pseudonym Nemo (Latin for ‘No one’). Mr Edwards did the second in 1984, the feature didn’t appear in 1985, and I did the next in 1986. That of 1987 was the last to appear because of a lack of willing contributors.

The third new feature, Retrospect, made its first appearance in October 1985. This article was to be mine because as editor I could refer to bound copies of most of the previous issues of the magazine going back to the very first one in the late 1860s. The idea was that I would look back at the St Augustine’s of 50 years before as revealed in the pages of those past editions. I didn’t write a Retrospect in 1988 and that for 1991 was the last. Being headmaster meant that I didn’t really have enough time to do the research or the writing.

It was in August 1987 that I took over as headmaster from Father Bernard, and that had to be the end of my editor’s career. My successor was the head of English, Mr Denis Fligg, who also became deputy head in due course. He produced six issues up to and including October 1993 but the last two issues, 1994 and 1995, did not make their appearance until after the school had actually shut in July 1995. They appeared just for the archives, not for distribution, but only because of the efforts of Mrs Sheila Mulvihill, the headmaster’s secretary, who typed up what there was and produced a few home-made copies on her computer. For those there was no real editor, but I wrote a Headmaster’s Editorial for each.

Over the years, several issues of the magazine were periodically incorporated into leather-bound volumes to make an elegant series. Each time three bound copies were made, one for the monastery library, one for the headmaster’s study and one for the editor’s reference and we were very fortunate that in the later years the book-binder was an Old Augustinian, Robert Paling (left in 1975, I think) and a splendid job he made of those volumes.

Every issue had a volume number and an individual number within the volume. When I became editor I could detect no method in the system – when did the editor start a new volume? When he felt like it, seems to have been the answer. Several issues of the magazines were bound when they formed a suitable thickness and I could detect no other criteria. So volume numbers bore no relation to the bound volumes. And that seemed crazy. I worked to alter that so that editions would be bound every five years, starting at the beginning of a decade, and volume numbers would correspond to bound volumes. I started that system in 1986, that edition being Vol. XVIII No. 1. Volume XIX started in 1991 and the school lasted just five more years to complete it. If there had been a 1996 for St Augustine’s, that edition would have been Vol. XX No. 1, but it was not to be.

SENIOR MASTER

If the late 1970s saw peak numbers of pupils at St Augustine’s, the 1980s saw a rather worrying decline set in gradually. In 1985 a report was ‘commissioned’ by the monastery and it was my task to write it and present it. I consulted staff and in due course drew up a comprehensive document about what might be done to improve the viability of the school. I analysed the situation and proposed various courses of action that could be taken – marketing, improvements in the amenities, etc. – and read the report to a combined meeting of staff and monks. The papers remained in the files and went over to the abbey when the school closed. Although I can’t remember the details, I am sure that the picture it presented was rather simplistic. I am not at all sure that in the end anything could have been done to save the school. We were off the beaten track, being tucked away in the bottom south-east corner of the country, and locally the market was neither rich enough, Catholic enough, nor big enough to provide us with large numbers of day-boys. Besides, there was St Lawrence College in Ramsgate as a nearby rival, with others not all that far away in Canterbury. Moreover, attitudes were changing so that boarding was no longer really in favour, and the publicity about cases of child abuse in boarding schools must have had a decidedly negative effect. Another factor was that the running down of Britain’s armed forces, particularly those abroad, meant that that market had shrunk significantly. Further, with the grammar schools still in existence in Thanet, local parents of bright children would automatically send them there so our day-boys were more likely to be 11+ failures, and yet we would be expected to get good examination results out of them. Quite often we did, but there were many forces at work against us.

Still, within the school there were things which could be done. As mentioned above, amenities could be improved, attitudes (staff, administration) changed, and discipline strengthened so that the most could be got out of the boys. As a move in that direction, at one of their termly meetings in 1986 the governors created a new post to give someone the authority to tighten up structures, practices and discipline where necessary.

“Have you got anyone on the staff who is suitable for the post?” Father Bernard was asked.

“I think so,” was his reply.

How do I know? Because I was present at the meeting in my capacity as teacher-observer. A couple of years earlier it had been thought more democratic for teachers to know something of what went on in governors’ meetings and so they were given the opportunity to elect one of their number to attend the meetings and report back to them. They had chosen me to represent the college but as for who represented the junior school, my memory fails me. Was it Mr Woodhams and then, later, Mr Wells?

After the meeting, Father Bernard asked me if I would accept the new post and I agreed. It must have been September 1986. What about my title? Robin Edwards was assistant headmaster, so I couldn’t be the deputy headmaster. Therefore I proposed the title of Senior Master. Father Bernard agreed, and I had a fairly free hand as to what I did. Most things were quite small. For example, at morning assembly in the school chapel, the boys would be seated in the benches waiting for it to begin. Father Bernard would walk up the centre aisle, look at the hymn board and announce the number of the hymn, which everyone could see, of course. That seemed to be the signal for the boys to stand. It had struck me that this was quite improper and that out of respect the boys should stand when the headmaster made his entrance. Now I had the authority to change it, and I did so. However, the most important thing I did (according to John Draycott, the Maths teacher, and he was probably right) was to introduce a spot-check on homework to see that it had been done and a satisfactory attempt made. I had a proper notice run off and I filled it in daily with the names of those I wanted to report to me with their work in a particular subject. I think it kept the boys on their toes as they didn’t know whose work I was going to ask to see.

My time in that capacity, however, was to be barely a year as in January 1987 I was appointed headmaster-designate to take over on 1st August. The post of senior master thus disappeared.

HEADMASTER

After the monks agreed in late in November/December 1986 to the retirement of Father Bernard as headmaster after 30 years in the post, Abbot Gilbert came to see me at home on Friday 2nd January and offered me the headship as from 1st August 1987. I accepted. That was a relief to Abbot Gilbert as he said that the monks did not know what they would have done if I had turned it down.

Prior to the governors’ meeting to confirm it, the usual notices were sent out, including the agenda. As the teacher-observer I received copies of these papers and I saw that after the formalities the first item was the appointment of a headmaster. I attended the meeting as usual, sitting at a small table with the teacher-representative of the junior school, separate from the governors as always. When the time came, I had to withdraw and went along to the empty staff-room. After about a quarter of an hour Father Bernard came in smiling and asked me to rejoin the meeting. In that short time, without my even being interviewed by the governors, the decision had been made. I suppose that most of them knew me quite well. For a start, the monks had a majority on the board and I was a familiar figure to all the other governors from my presence at their previous meetings.

At the same time as I became head of the senior school, Father Augustine Coyle took over as headmaster of the junior school. As Brian Coyle he was a pupil at St Augustine’s when I joined the staff and I taught him English. He entered the monastery in Ramsgate, taking Augustine as his monastic name, and was ordained priest in 1984, the first Old Boy of the college to become a Benedictine priest at Ramsgate since Father Bernard himself over thirty years earlier.

Above us both was the principal, the person with overall responsibility for the two schools who was answerable to the monastery for the whole establishment and by the very nature of the position, the principal would always have to be a monk. Though he had stepped down as headmaster of the college, Father Bernard retained the office of principal though when he went to Israel for a nine-month sabbatical shortly after relinquishing the headship, Father Benedict was appointed acting-principal.

Becoming headmaster meant that of necessity I had to relinquish certain other responsibilities which I had acquired over the years, including my editorship of the school magazine. During that time my alter ego, Scribbler, was born to sit alongside Silly Mid-on. Scribbler lived on until 1991 though only as the author of the Retrospect articles, while Silly Mid-on continued fielding (and batting) until 1994. Scribbler’s daily chore of the diary, however, had had to go. The new anonymous diarist (for just couple of years) was Father Stephen Holford. He was not new to the role of Diarist as he had been the compiler years before prior to my joining the staff.

FATHER STEPHEN HOLFORD

Father Stephen returned to the abbey at the end of my first academic year at St Augustine’s College in 1972. I think that was when he became parish priest at Minster, where he remained for some years, then was the prior at the abbey for a while. In due course he returned to teach at the school, though on a part-time basis.

I have already mentioned that early on in my career at St Augustine’s I had unintentionally upset Father Stephen but there were also other occasions when I was on the receiving end of his criticism. I didn’t mind that as I knew it was always courteous and well-intended, and usually had some justification.

The first of these arose out of my editorship of the school magazine. At the time Father Stephen was at the abbey and it might well have been during his time as the prior. He was a contributor to the magazine with his article entitled Community Notes, a feature in every issue of the magazine containing news about the monks and events at the abbey. His pseudonym was Dom Tepidus. His choice of pseudonym says something about his humour and perhaps about his honesty, even where his opinion was perhaps erroneous. He might claim that as a monk his faith or monastic observance was tepid but that does not mean that it was. As a young man he went through a time when he did not believe in God, but eventually he came to the Faith. His practice of it never struck anyone as being tepid – that was his humility speaking.

Having sent me his Community Notes, he wrote a short letter (dated 21st July 1985) with additional information and a suggested amendment, but his concluding remark showed his unduly sensitive side. He wrote:

“I look on my feeble contributions more as raw material and have never forgotten (how could I?) that my first effort under your editorship had to be prefaced with an editorial disclaimer. That was in 1972. 13 years later the wound still smarts!”

The issue in question was that bearing the date 1971-1972 which covered the first year of the school in Westgate. A record of the school year in the form of a diary was a feature of the magazine throughout the whole time that I was at St Augustine’s, and before my time too. However, on this occasion there was no diary as such but instead Father Stephen wrote a review of events, a lengthy piece entitled Chronicle. Having read it, I felt it necessary to write an editorial comment at the beginning to try to moderate the effect (the preface referred to in Father Stephen’s letter) because a school magazine is a public relations presentation and not a place to expose one’s weaknesses or failings. There has to be a difference between the reality of a school and the public image it wishes to present. What I wrote was:

“In this issue the customary Diary has been replaced by the Chronicle, and here everything is revealed from one point of view. Regular readers of the magazine will be familiar with the style of our Diarist, his deliberate exaggerations and distortions, his irony as well as his humour, or as a vehicle for it. But the picture is incomplete. To quote from the Chronicle: “The year has been, on the whole, a fair mixture of misfortune and advantage, of moderate success and painful failure.” The editor feels that the article stresses the ‘misfortune’ and ‘painful failure’ rather than the other aspects, and does not contain the ‘fair mixture’ that the year itself contained. Our Chronicler’s praise, where it occurs, is generous, his criticism scathing.”

My reply to Father Stephen’s letter urged him to read instead the words which I had written about him in the editorial of that same issue of the magazine, for I said it“… owes a great deal to Father Stephen as the Diarist for the past few years. He has injected a liveliness into this part of the magazine which was missing in the rather pedestrian recording of events in the Diary (to which it seems we may have to return) before it became his responsibility. Further, he has been that sort of contributor invaluable to an editor – a willing one. He never really needed to be reminded that his contribution was required, and it was always among the first to be received. Furthermore, his assistance in the production of the magazine has been invaluable to me. He takes with him my sincere thanks for all his efforts.” However, at the very least I had been thoughtless and should have approached him directly about it. I am sure he forgave me – he was too good a Christian not to. If I ever doubted that, a letter he wrote to me in August 1987 with its warm salutation “My dear Kevin,” confirmed it. I have reproduced the letter here to give an idea of the style of Father Stephen for those who may not have known it.

Immediately following Father Stephen’s article in that magazine is a retirement tribute delivered by Robin Edwards. It is an extended cricketing metaphor. If you have that issue, you will find that both items are well worth reading. Father Stephen’s reference in the letter to my own vale in 2017 is a typical touch of Stephenian (does ‘Holfordian’ sound better?) wry humour. The significance of the year is that 2017 would mark 30 years since I became headmaster, corresponding to Father Bernard’s actual 30 years in office. He knew very well that I would serve nowhere near that length of time on account of my age but he was right to think that he would not be ‘on hand’ then. As for gathering material for writing my Vale in stages, that too was his fanciful imagination at work – there would be little to collect, sift, and collate and it would not be long enough to need writing in stages. Even Father Bernard warranted just a page and a half of the magazine. Thanks for the thought, Father Stephen – it gave me much amusement as you probably intended. Perhaps, though, Father Stephen was being prophetic and sub-consciously referring to my ultimate ‘vale’. We’ll find out in about two years. If it is, I hope it will be followed by the ultimate ‘salve’.

On another occasion, however, I was again on the receiving end of Father Stephen’s criticism. It was during the early part of my time as headmaster. In that capacity I read all of the end-of-term school reports written by teachers which would be sent out to parents and then would add my own comments at the end of each one. It was my practice afterwards to write a brief Report on the Reports, in effect my criticisms of what had been written. In this I drew attention to mistakes and errors of English as well as what I considered to be deficiencies in them. The reports conveyed an image of the school to parents and, therefore, should show us as teachers to be knowledgeable and able to pass on that knowledge. My Report on the Reports for the Summer Term 1989 was broad and brief, just two-thirds of an A4 page, and Father Stephen responded to it with a three-page A4 letter to me analysing where he thought I was wrong in my criticisms and my expression of them. I intended to respond in detail but I have only a rough draft of my would-be reply so I don’t know now whether I actually sent a written reply to him but made no copy of it or whether we had a face-to-face conversation about things instead. Perhaps it was both.

Towards the end of his life Father Stephen went to Ghana to spend a year at Kristi Buase monastery, which had been established by monks from Ramsgate, Prinknash and Fort Augustus at the request of the local bishop. He came home from there on health grounds, having lost a lot of weight. I think that the reality was that he had developed the cancer of which he died on 24th October 1997 aged 76. The end came relatively suddenly. On the Monday he started clearing his room at the abbey and on the Friday he died. It was as if he had known the end was near. He was a fine man and, so far as I could judge, a fine monk.

MORE MONKS

Another monk who looms large in my memory is Father Theodore Richardson, who died in January 1988 at the beginning of my second school term as headmaster. He was only 70. Who can forget his sermons at the weekly school Mass on Fridays? It wasn’t their content that we found memorable. That probably didn’t stay long in our minds once we were out of the chapel, but the length and depth of his homilies did. That they were delivered without notes yet were perfectly constructed made a lasting impression.

There were two other great pipe smokers among the monks, Father Benedict and Father Bernard himself. Then one day, whether in the 1970s or 1980s I don’t remember, I realised that Father Bernard wasn’t smoking any more, and this persisted until it became obvious that he had given it up. I don’t know why he did and I never asked him. What I did ask him eventually was whether he missed it. “Very much,” was his succinct answer. He didn’t weaken as I had and he didn’t smoke again. I wonder if he kept his pipes, though. I kept mine and I still have them but I am never tempted to bring them back into use.

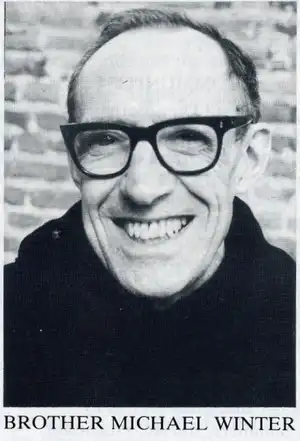

Almost exactly a year after Father Theodore, Dom Michael Winter died at the age of 82. He had a sense of humour but it wasn’t subtle or acerbic, just ordinary. Nor was he an intellectual giant but he had that same human touch with the juniors that I had seen in Father Theodore. Brother Michael ran the book-room very efficiently for many years and in that capacity probably had close contact with every boy who passed through the school. The book-room too proved to be a place of refuge as when it was open during breaks and at lunch time there were usually numbers of small boys crowding in front of the counter and sometimes squeezing behind it. I think they plagued Brother Michael, perhaps trying to get pencils or rubbers on credit, but he was no soft touch and probably quietly enjoyed their pestering him.

ANOTHER DEATH

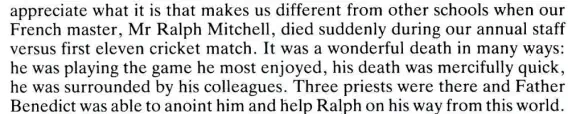

Six months after Father Theodore died in January 1988, in July, came another death, that of Mr Ralph Mitchell, who was still a relative newcomer as he had come to St Augustine’s in September 1986 to teach French. Instead of relating the circumstances from the distance of 2015, perhaps the best thing to do is quote from my tribute appearing in the October 1988 issue of the magazine. It began: “Ralph Mitchell had been with us for just two years when, at the age of 58, he suffered a heart attack on July 6th, just a few days before the end of the summer term. The circumstances added to the shock for it occurred during a cricket match between a Staff XI and the Abbey School. Ralph bowled a typical off-break and then suddenly it was all over. Medically nothing could be done for him, but he was anointed in accordance with the Last Rites of the Church, and in the Chapel all joined in prayers for the repose of his soul.”

I went on to say that “He was a gentle person, respected by the boys even when they took advantage of that gentleness,” concluding with “… his example in the practice of his religious faith will be the greatest loss to the school.”

I hadn’t been present at the match as it was a junior school event but twenty minutes after Mr Mitchell collapsed Father Augustine rang me at home to tell me the sad news. I went over to the school immediately and joined in the prayers in the chapel – the Rosary was being said, if I remember correctly.

The death must have made a profound impression on the boys in particular and I have no doubt that it will be deeply etched to this day in the memories of those who were there. May he rest in peace.

Remembering these and others of our colleagues who have died is not at all morbid as it is their warm and human qualities that are being brought back to the front of the mind. May they all rest in peace.

NEW BROOMS

In 1988 there was also a new broom to replace Abbot Gilbert Jones at the abbey in Ramsgate. Abbot Gilbert, abbot since 1972, had been elected Abbot President of the Subiaco congregation of Benedictines with his base in Rome so he had had to relinquish the office of Abbot of Ramsgate, which thus became vacant. The community elected Father Bernard abbot in his place, which brought further administrative change for the school as Abbot Bernard had to relinquish the post of principal of the schools and assume the honorary role of President of the combined school as all abbots did. The office of principal was now vested in Father Benedict and a year or so later Father Augustine was given that responsibility in addition to his duties as headmaster of the junior school. That meant he was both my equal (as headmaster) and my superior (as principal).

Father Bernard had had the flood to contend with in 1973, relatively soon after the school moved to Westgate, and similarly just a couple of months after we had taken on our new responsibilities, Father Augustine and I were faced with the aftermath of another natural disaster – the so-called hurricane in October 1987. Father Stephen as Diarist wrote a brief but graphic account of the impact of it on the school. It began: “The hurricane gripped Westgate at 2.00 a.m., the phone was off, the lights were off, the tiles were off, the trees were down and the boys were up as things got worse and worse…. ” while the Editorial by another hand states that “ … many a heartfelt prayer for preservation was directed to the Lord.” It must have been bad. It was. But the damage was repaired.

Fortunately no other natural disasters afflicted us and my experiences as headmaster were for the most part routine. Discipline was not a serious problem and probably at this time it was the best it had ever been. Father Bernard had used corporal punishment where he judged it necessary but my attitude was quite different and I never used it once nor was even tempted to. I think I might have found it almost impossible to give a boy the cane. Of one thing I was certain and that was that discipline was not dependent on a readiness to use corporal punishment and might, indeed, be better without it. Most of the boys had a strong loyalty to the school and the spirit was excellent and I think that was partly due to what I hope was a relaxed, kindly but firm regime.

Disciplinary problems did, of course arise and occasionally I had to suspend a pupil or even, rarely, expel a boy. One of these cases involved a pupil from Africa. I considered that he was a ‘heavyweight’, a bully, and an undesirable character, so I called in his mother to take him away. She was smart and well-spoken and gave a favourable image, even giving the impression that she was understanding and supportive of the school. That was simply to try to ‘charm’ me into retreating from the position I had taken, but when it became clear that I was standing firm, her tone changed and she took the ugly step of accusing me of racism, which I considered ironic as I had spent 9 years teaching in two mission schools in East Africa in the 1960s. It was really bluster on her part, but unpleasant nevertheless, and it merely succeeded in being counter-productive as it simply hardened my attitude. She went, and so did her son.

Another problem that had always existed was the non-payment of fees by some parents. With one from Sandwich, I eventually had to take a hard line and ask for the boy to be removed until the fees were paid or at least until some effort had been made to reduce the amount outstanding. The mother’s line of action was to write to Abbot Bernard protesting at some length that she had every intention of paying the fees and accusing me of being ‘a little Hitler’ for pressing for payment. That didn’t work either. Abbot Bernard knew all about such problems.

A headmaster, of course, not only has to deal with pupils (and parents) but staff as well, including interviewing applicants for any vacancies that arise. Given the structure of St Augustine’s, Father Augustine and I conducted joint interviews, whether it was for a post in the senior school or for one in the junior school. In the senior school in 1989 we had a vacancy for a language teacher. One of the applicants for that was Mr Mark Greenwood, a tall young man in his mid-20s. He was not a Catholic but he came across very well and we offered him the post, which he accepted. It was not long before he was received into the Church and then the school lost him as he decided to enter the monastery to try his vocation. He stayed, was professed and then ordained. Now he is Abbot Paulinus Greenwood, 8th Abbot of Ramsgate and 1st Abbot of Chilworth.

BENEDICTINE HEADMASTERS’ CONFERENCES

It was probably some time during the 1970s that the practice had been established of the headmasters of Benedictine schools meeting annually to discuss matters of common interest, a different school or monastery hosting the event each year. In 1985 it was held at St Augustine’s.

To begin with all of the heads were monks but my first meeting in 1987 was different as there were three lay headmasters. The head of St Benedict’s, Ealing, was Dr Anthony Dachs, who had previously been the deputy head at Stonyhurst College, the Jesuit school in Lancashire, while Mr Graham Sasse was the head of Gilling Castle, the preparatory school for Ampleforth and just across the valley from it some twenty miles north of York. I was the third. That year it was the turn of Buckfast Abbey to organise the event and so Father Augustine and I made our way to Newton Abbot by train, meeting two or three others who had caught the same one as us. We were met at the station and taken to Buckfast, which is renowned for its tonic wine and honey. Those delights, and the visitors who came to sample them, were, and probably still are, its main source of income. The abbey is in a rather scenic location, which also helps to make it an attractive day-trip destination for holidaymakers in the area.

Buckfast Abbey School was a preparatory school and so, of course, it acted as a feeder mainly for its Benedictine older brothers. We were given a tour of it, which was always a feature of these gatherings, and I liked what I saw. One thing that struck me was that the Buckfast boys addressed their headmaster, Dom Benet Conlon, as ‘sir’ not ‘Father’. That seemed to be the convention in the schools of the English congregation. Father Benet was a warm fatherly figure, obviously liked by the boys and one who liked them, so somehow ‘Father’ would have been much more appropriate.

We were accommodated in the abbey itself, the rooms being clean, plain and adequate, as one would expect. We had breakfast in the monks’ refectory, and of course we laymen were subject to the same rules as the monks themselves. That meant we served ourselves, ate in silence and cleared away our own plates, etc. Coffee wasn’t drunk from cups but from bowls, and that seemed to be the case in most of the other abbeys I went to in later years. Sometimes on these conferences we had lunch or the evening meal with the community, and then we encountered the practice not only of silence but of one of the monks reading aloud, either from religious works or from secular literature. There was never any reading at breakfast, however.

Built into the conference programme was time for the visiting monk-headmasters to participate with the local community in Vespers and Compline in the evening, and we laymen were free to attend or not as we wished. If we did, we joined the monks in the choir stalls and weren’t ‘banished’ to the nave. We usually went and I found these occasions, at whichever abbey we were, devotional, inspiring, and deeply spiritual experiences. The relative darkness of the churches at that evening hour added to the atmospheric effect. It seemed easy to be holy in such places, but I suppose it never is. There wouldn’t be much merit if it were.

Naturally it was the heads of the leading schools, Ampleforth and Downside, who seemed dominant. These were Father Dominic Milroy and Father Philip Jebb respectively and I found both of them impressive in different ways. Father Dominic came across as being almost aristocratic; there was certainly style in his manner but a warmth as well.

The headmaster of Douai in Berkshire was Father Geoffrey Scott, who came from somewhere near Newcastle. He also was new to the position but just a few years later he became Abbot of Douai. Similarly, Father Stephen Ortiger of Worth Abbey’s school near Crawley in Sussex, was elected abbot of his monastery somewhere about the same time. Both of these struck me as being likeable and efficient as well as approachable, Abbot Stephen even writing a letter of commiseration to me on hearing of the closure of St Augustine’s. Altogether I was impressed with the quality of these Benedictine heads and their schools.

The meeting at Buckfast had no outcome and none of the conferences ever had had in the past nor did in the future. It wasn’t intended or expected that they should. That didn’t make them a waste of time because they were as much social events as anything else. It was a good thing for us to get together, to get to know each other and to learn something about each other’s schools. However, since they were all different in style and character and had different problems, weaknesses and strengths, there could be no such thing as a common policy. Only one corporate venture was ever undertaken and that was a Benedictine joint stall at an independent schools’ fair in London in November 1989. For that most of our separate schools provided their own prospectuses and literature as well as material for display, and we shared in the manning of the stand. It was good for solidarity rather than for business.

In 1988 the meeting was nearer home, being at Ealing. What set St Benedict’s apart from all the other Benedictine schools was that it was a day school and in an urban area, but even here the atmosphere in the church, which was a short distance away from the school, was striking, particularly at the early morning conventual Mass when the whole of the small congregation gathered with the monks around the altar at the consecration.

The following year again saw us travelling further afield as our next destination was Fort Augustus Abbey in Scotland. Father Augustine and I flew from Gatwick to Inverness, where we were met at the airport by a Brother Robert. His driving was, shall I say, rather ‘frantic’, which might have distracted a little from the scenic quality of the journey, which took us from the top end of Loch Ness to the bottom, where the abbey was situated on a small promontory looking straight up the loch. It was idyllic – at least when the weather was glorious.

Of all the schools and abbeys, Worth, where we went in 1990, was the most modern, not looking like a traditional abbey at all. The church, for instance, was a circular brick building with a concrete roof. It was jokingly said to look like a flying saucer when seen from an aeroplane coming into or taking off from Gatwick airport. Perhaps it does give that impression, but I found it attractive inside. Brick can give a beautiful finish and it did so here. The concrete roof was over a lantern structure to let light in through plain glass and it didn’t disturb at all.

In contrast, Downside, where we met in 1991, was more traditional while Belmont, near Hereford, was a mixture. At the latter the abbey church was old, small and intimate whereas the school seemed to be more modern. Usually these meetings took place in November, but for some reason Belmont couldn’t take us at that time in 1992 so the meeting was in January 1993 instead.

Having a meeting in January 1993 meant that we had two gatherings that year because we moved back to our customary month of November for our next one, which was at Glenstal in Ireland. Again a flight was involved, Father Augustine and I flying from Stansted to Shannon, near Limerick. This wasn’t without incident as no sooner were we in the air than the captain came on the public address system to tell us in a totally matter-of-fact manner that the control tower had seen what appeared to be smoke coming from one of our engines so he was going to return to Stansted as a safety measure. Everybody remained perfectly calm. Twenty minutes later we disembarked for the necessary checks to be made, boarded a different plane and took off once more about an hour later. No harm had been done – we were just delayed a little and that was all. Despite being so late landing at Shannon, we were met and driven to Glenstal, where we were hospitably treated as always.

It had been a privilege to be almost a part of the monastic community during those two or three days of the meetings, and one particularly abiding memory is that of participating in Compline in the modern abbey church at Worth. Modern it might have been but at Vespers and Compline in the dark of the evening, with just the dim lights in the choir, it was particularly atmospheric as the monks entered in procession and this feeling was intensified by the Gregorian chant of the Office.

THE DECISION TO CLOSE

The closure of St Augustine’s and the junior school in July 1995 was largely attributable to the financial situation, though some monks were ideologically against independent schools while others were supportive, which I think had always been the case. Nevertheless, I could see that it was quite possible and reasonable that monks who supported the school might, with regret, favour closure on financial grounds. Abbot Bernard himself came into this category.

The financial situation was undoubtedly precarious and the abbey had been subsidising the school for two or three years. The number of pupils had declined steadily over a period of time for the various reasons mentioned earlier – there was the national trend against boarding, the reduction in the number of Britain’s servicemen overseas, the competition from other independent schools in the area, and the fact that Thanet itself was a small ‘market’ because it is a relatively poor area. In addition there were our own failings, which Father Augustine and I were supposed to be doing something to eradicate. Even when junior numbers increased under Father Augustine, the rise was mainly in day-boys, many of whom had been admitted on favourable terms or on ‘scholarships’. So the larger number of pupils in the junior school was deceptive as it did not mean that there was a proportionate increase in income from fees. Also, a larger number of academically weaker pupils had implications for future examination results, and yet we had to be seen to be performing well. Statistics would only reveal the outcome and not the quality of the material to start with, but poor results would certainly make us less attractive to parents.

So things came to a head and from about Easter 1994 onwards there were frequent meetings of the governors to discuss the situation. Though they were normally held once a term, now they became almost monthly, but as time passed it became clear what the likely outcome would be.

One of the nuns of the Ursuline Convent was always on our board of governors and at this time it was Sister Dolores Caine until she was transferred to another convent and was replaced by Sister Mary Murphy, the headmistress of the Ursuline Convent School, who was going to retire from that office at Easter 1995 after having carried the burden for 18 years. I had known her for some years and I found her a charismatic figure whom I liked very much. Her first governors’ meeting was in November and at this one it became quite clear that the closure of the school was virtually certain. Sister Mary’s immediate reaction was that something had to be done for the boys, who would otherwise have their education disrupted, some at a crucial stage in that they would have to find new schools in the middle of their two-year GCSE and A Level courses. Her solution was that the convent school should become co-educational and absorb all the boys who wanted to transfer to it. This would also save the jobs of some of our teachers as the Ursulines would need additional staff. The decision wasn’t up to her but she was confident that her community would support this radical proposal. At last there was a gleam of light in all the gloom.